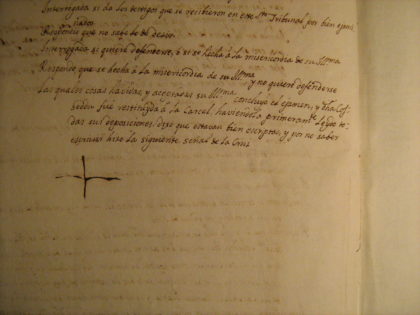

A trial for superstition and witchcraft in 1735 in Alghero.

Our story is set in the XVIII century, in Alghero, enclosed in the old town, defined by the harbour, by the countryside, from here you come and go, crossing the town gateway. People move around the alleys, through churches and buildings, where the population lives, stops by and makes small talks by the windows, at night men take shelter in taverns, looking for some consolation after a hard day at work. Throughout these places, people observe each other, listen to each other and share experience with each other. It is like if those men and women were still there, in some corner of the Alguer vella (the old Alghero), at the crossroad of the alleys, muttering in the streets, exchanging news and information.

During the day is very noisy all around, the main street heaves with people coming and going, you can hear the shouts of the peddlers, bells, horses hoofs, the kids laugh and play in front of the houses while women hang their laundry in the sun, and the fishermen roll up their nets. Life is scanned by the work activities: fishing, the trade in the harbour and then agriculture and animal farming. The soldiers community is a very important presence, they are so many in town. Military expeditions towards the hinterland depart from here and the ones who stay are employed in continuous patrols on the bastions, in the changing of the guard or in supply procedures.

During the day is very noisy all around, the main street heaves with people coming and going, you can hear the shouts of the peddlers, bells, horses hoofs, the kids laugh and play in front of the houses while women hang their laundry in the sun, and the fishermen roll up their nets. Life is scanned by the work activities: fishing, the trade in the harbour and then agriculture and animal farming. The soldiers community is a very important presence, they are so many in town. Military expeditions towards the hinterland depart from here and the ones who stay are employed in continuous patrols on the bastions, in the changing of the guard or in supply procedures. Maria Cosseddu was a common woman, she lived in town and has been taken to trial from the Episcopal Inquisition Court in 1735, for witchcraft and superstitious remedy, used to nurse diseases. Her healer activity, combined with formulas, ritual and materials acquired from the catholic religion, often smuggled from churches and graveyards, was unacceptable for the ecclesiastical authorities and was condemned as superstitious; it was considered dangerous, as it was adverse to religion and for this reason prosecutable. Maria’s remedies implied a relationship between a single person with the holy. This was not approved by The Church and represented a danger of sin and heresy, by provoking the survival of ancient superstitious practices that the Institutions were trying to eradicate. Maria was the mediator between man and divinity, this way, she was depriving The Church of its authority, power and control over its actions. All this risked to be a source of deceit and fraud, as well as in disagreement with the official doctrine.

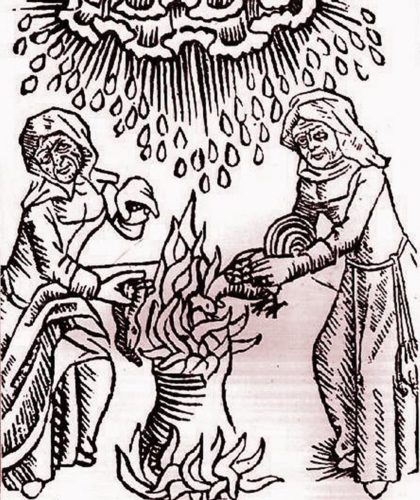

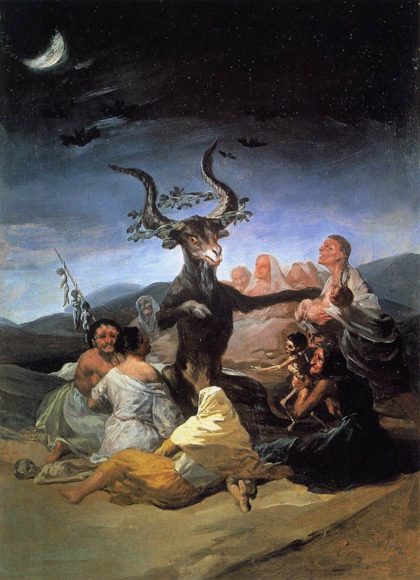

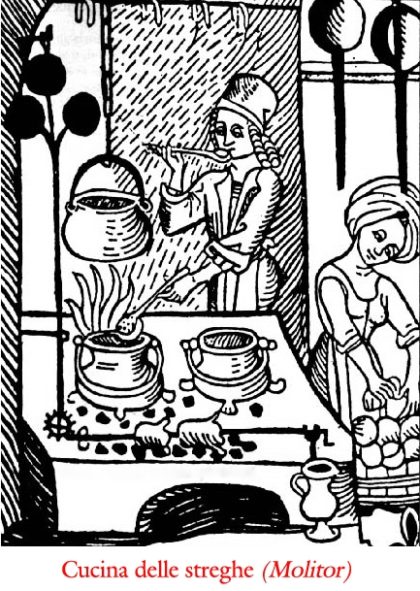

Maria Cosseddu was a common woman, she lived in town and has been taken to trial from the Episcopal Inquisition Court in 1735, for witchcraft and superstitious remedy, used to nurse diseases. Her healer activity, combined with formulas, ritual and materials acquired from the catholic religion, often smuggled from churches and graveyards, was unacceptable for the ecclesiastical authorities and was condemned as superstitious; it was considered dangerous, as it was adverse to religion and for this reason prosecutable. Maria’s remedies implied a relationship between a single person with the holy. This was not approved by The Church and represented a danger of sin and heresy, by provoking the survival of ancient superstitious practices that the Institutions were trying to eradicate. Maria was the mediator between man and divinity, this way, she was depriving The Church of its authority, power and control over its actions. All this risked to be a source of deceit and fraud, as well as in disagreement with the official doctrine. Cosseddu used to whisper some formula: this was very efficient for the ritual, as the low volume of her voice and the obscurity of her words made stronger the perception of mysterious energies in action and thus the power of the healer. Among several ‘ingredients’ she used the heart, a vitality symbol, of a black animal, colour that evoked the world of the dead and its powers. You can infer from some of her practices her relaxed connection with the dead and the afterlife, a very ancient custom that was kept under a strict control by The Church. The most wanted deceased to carry out remedies and medicaments, were the ones killed by a violent death. The latter were often pictured, by the living, trapped in a limbo and eager for revenge, they were generally used for black magic rituals. The popular belief was that they could allow a contact with the afterworld and its powers. The practice of using bones coming from dead bodies has been documented for centuries, present in the Middle Ages folk medicine and in Modern Times. It would appear that the dead’s bones would take over the illness to destroy it. Some of these ancient customs have lasted until today, like the prayers against the evil eye, some others, like the use of the dead’s bones, we preserve just the memory of the past. The accused healer never implies the evil component during her rites, she does not mention or invoke the Demon. Maria declares that all her treatments pull their strength from the invocation of Saints and the Virgin; her actions were combined with prayers and orations and her medications were preceded by a sign of the cross: it looks like she is sure to act for the good, with unusual methods that nevertheless are religious dynamics recognised by everybody.

Cosseddu used to whisper some formula: this was very efficient for the ritual, as the low volume of her voice and the obscurity of her words made stronger the perception of mysterious energies in action and thus the power of the healer. Among several ‘ingredients’ she used the heart, a vitality symbol, of a black animal, colour that evoked the world of the dead and its powers. You can infer from some of her practices her relaxed connection with the dead and the afterlife, a very ancient custom that was kept under a strict control by The Church. The most wanted deceased to carry out remedies and medicaments, were the ones killed by a violent death. The latter were often pictured, by the living, trapped in a limbo and eager for revenge, they were generally used for black magic rituals. The popular belief was that they could allow a contact with the afterworld and its powers. The practice of using bones coming from dead bodies has been documented for centuries, present in the Middle Ages folk medicine and in Modern Times. It would appear that the dead’s bones would take over the illness to destroy it. Some of these ancient customs have lasted until today, like the prayers against the evil eye, some others, like the use of the dead’s bones, we preserve just the memory of the past. The accused healer never implies the evil component during her rites, she does not mention or invoke the Demon. Maria declares that all her treatments pull their strength from the invocation of Saints and the Virgin; her actions were combined with prayers and orations and her medications were preceded by a sign of the cross: it looks like she is sure to act for the good, with unusual methods that nevertheless are religious dynamics recognised by everybody. The figure that shines through the documentation is the one of a poor woman, homeless,unemployed, who does different kind of jobs for living, for example the spinner and the bread-maker, always in need of support. A woman of the people, illiterate, guardian of practices and beliefs passed on generations, thanks to which she tried to ease the pain of some people and pleased the desires of others, since you could not trust science and technology yet, this way she would certainly make a living. An old woman, for her days, a unique and unusual character, cherished and criticized at the same time; we cannot know more about her ethical qualities or her facts, we cannot judge her today, but understand her figure, placing it in the different context and dynamics of her era. We enjoy picturing Maria on the narrow streets within the walls, her face marked by wrinkles of time, bowed by the weight of the years and the stories she lived. She wanders around an ancient world that does not exist anymore, crowded with people, overflowing with life, love, pain, suffering, fears and poverty, heaving with stories, in the babel of faces, in the noise of the alleys.

The figure that shines through the documentation is the one of a poor woman, homeless,unemployed, who does different kind of jobs for living, for example the spinner and the bread-maker, always in need of support. A woman of the people, illiterate, guardian of practices and beliefs passed on generations, thanks to which she tried to ease the pain of some people and pleased the desires of others, since you could not trust science and technology yet, this way she would certainly make a living. An old woman, for her days, a unique and unusual character, cherished and criticized at the same time; we cannot know more about her ethical qualities or her facts, we cannot judge her today, but understand her figure, placing it in the different context and dynamics of her era. We enjoy picturing Maria on the narrow streets within the walls, her face marked by wrinkles of time, bowed by the weight of the years and the stories she lived. She wanders around an ancient world that does not exist anymore, crowded with people, overflowing with life, love, pain, suffering, fears and poverty, heaving with stories, in the babel of faces, in the noise of the alleys.

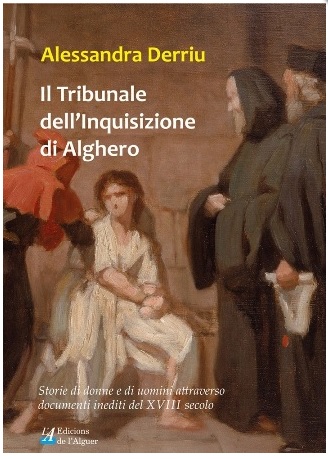

Alessandra Derriu

Based on A. Derriu, Il tribunale dell’Inquisizione di Alghero. Storie di donne e di uomini attraverso documenti inediti del XVIII secolo, Alghero 2015.

Based on A. Derriu, Il tribunale dell’Inquisizione di Alghero. Storie di donne e di uomini attraverso documenti inediti del XVIII secolo, Alghero 2015.

Alessandra Derriu (Alghero, 1979). BA in Conservation of Cultural Heritage, at the University of Sassari, MA at the Archive School of Rome, palaeography and diplomatic of the Vatican Secret Archive. She worked at the Archive of the Municipality of Alghero, the Archive of the Alghero-Bosa Diocese and the Archive of Simon-Guillot family. Recipient of a research scholarship from the Sardinian Region, at the History Department of the University of Sassari, she carried out a study on Sardinian Medieval history, taking care of the sources editions, on paper and online, publishing Atti contabili della villa di Alghero (mandati e ricevute di pagamento anni 1405-1415), 2005; Alghero e i suoi privilegi in alcuni documenti inediti del XV secolo, 2007; Gli atti notarili del XV secolo dell’Archivio Capitolare di Alghero, 2009; L’Inventario dell’Archivio del Capitolo Cattedrale di Alghero, 2013; Il tribunale dell’Inquisizione di Alghero. Storie di donne e di uomini attraverso documenti inediti del XVIII secolo, 2015. Other topics of her studies are the administration of justice in the Catalan-Aragonese Sardinia and trials for witchcraft and superstition. She is an archivist at the Historical Diocesan Archive of Alghero and history teacher at Escola de alguerés P. Scanu (Catalan –Algherese school).

English version: Francesca Sanna